The Immortal 600 at Gettysburg

Most of the approximately 5,000 Confederate prisoners who were captured at Gettysburg, including Brigadier General James J. Archer, were sent to Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, just south of Wilmington in the middle of the Delaware River. Some of those prisoners would eventually be sent to prisons at Point Lookout (MD), Elmira (NY), or, like Gen. Archer, to Johnson Island (OH). But in August of 1863 there were a total of 12,500 prisoners at Fort Delaware which, even after a recent expansion, was designed to hold just 10,000.

The enlisted men felt the brunt of the overcrowding at Fort Delaware, also enduring forced labor and a variety of forms of torture and mistreatment. But the officers lived in relative comfort. For many, that would change by the next summer, however, as those officers would get caught up in a drama that was unfolding more than 600 miles to the south.

The First 100

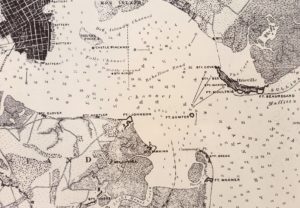

The port city of Charleston, South Carolina, had been hotly contested since the first shots of the Civil War were fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in April, 1863. Among the Confederate defenses which ringed the harbor was Battery Wagner on Morris Island, protecting the southern entrance to the harbor.

In July of 1863 several attempts to capture “Fort” Wagner had failed - including one led by the 54th Massachusetts as depicted in the movie, Glory - but the island continued to be the focus of Union bombardment. In the early morning of September 7th, the Confederates finally abandoned the island, and Union batteries quickly took up positions there. With this foothold in the harbor, the bombardment of the city of Charleston intensified.

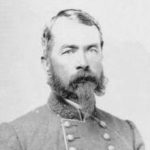

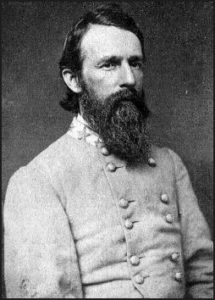

By June of 1864 the Rebel stronghold had been under constant siege for more than nine months. The Confederate commander in Charleston was a Virginia native, Major General Samuel Jones, a graduate and former instructor of artillery tactics at West Point.

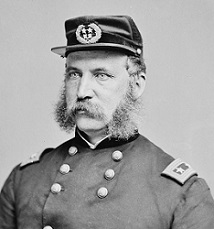

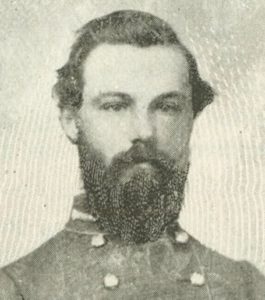

He was facing Union forces under command of Major General John G. Foster, a native of New Hampshire and a decorated veteran of the Mexican War. MajGen. Foster, too, was a graduate and former instructor in engineering at West Point. Although their tenures at West Point did not overlap, their respective areas of expertise would make them formidable foes in the standoff that was coming.

On June 13th, 1864, Confederate MajGen. Jones notified his counterpart, Union MajGen. Foster, that 5 Union generals and 45 field officers were being held prisoner within the city of Charleston “for safe keeping.” MajGen. Jones continued, “It is proper, however, that I should inform you that it is a part of the city which has for many months been exposed, day and night, to the fire of your guns.” In other words, Confederate MajGen. Jones hoped to use these Union officers as human shields.

Among these 50 Union officers were as many as 11 veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg.1 The most senior of these was BrigGen. Alexander Shaler, who would later receive the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Second Battle of Fredericksburg. At Gettysburg, Shaler commanded the 1st Brigade, 3rd Division, 6th Corps, which helped to hold the Union right flank at Culp’s Hill on the morning of July 3rd, 1863. Ten months later he was captured while trying to rally his men against a flank attack at the Battle of the Wilderness.

Only 1 of the Union officers in the group of 50 had been captured at the Battle of Gettysburg. He was LtCol. John P. Spofford of the 97th New York Infantry. On the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, LtCol. Spofford famously charged the North Carolinians of Iverson’s Brigade without orders, capturing about 400 Confederates and their colors. But a short time later the Rebels returned the favor, and LtCol. Spofford found himself on the way to Richmond’s Libby Prison. After about six months at Libby, he escaped through a tunnel, along with more than 100 other prisoners. LtCol. Spofford got 28 miles from Richmond but was recaptured and, after a stint in another prison camp in Macon, Georgia, was now among those who were helplessly facing friendly fire in Charleston.

Union MajGen. Foster protested that the use of these prisoners of war as human shields was a violation of the laws of war and described it as an “indefensible act of cruelty.” He rightly asserted that the notice from the Confederate commander was a ploy that “can be designed only to prevent a continuance of our fire upon Charleston.” In fact, the Union officers were being held in the extreme west end of the city; an area that the Federal guns were not targeting at that time. They were, therefore, not in the line of fire as MajGen. Jones had claimed. But Union MajGen. Foster did not know that his Confederate counterpart was bluffing.

Rather than be intimidated, Union MajGen. Foster retaliated by arranging to have 50 Confederate officers transferred from the prison at Fort Delaware to Morris Island. He warned his Confederate counterpart that, unless the Federal prisoners were withdrawn from Charleston, these 50 Confederate officers would be placed in a position that would expose them to the incoming fire of Rebel guns.

Those 50 Confederate officers included as many as 26 who had participated in the Battle of Gettysburg. Among the notables was MajGen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson and BrigGen. George H. “Maryland” Steuart, both of whom had been captured at Spotsylvania Courthouse in May of 1864.

Only 3 of the Confederate officers in the group of 50 had been captured at Gettysburg. They were BrigGen. James J. Archer (Archer’s Brigade, Heaths’ Division, 3rd Corps), Col. William H. Forney (10th Alabama Infantry, Wilcox’s Brigade, Anderson’s Division, 3rd Corps), and LtCol. Thomas C. Jackson (G. T. Anderson’s Brigade, Hood’s Division, 1st Corps).

When the Confederate prisoners arrived in the vicinity of Morris Island, the stage was set for a showdown. For two weeks Confederate MajGen. Jones and Union MajGen. Foster exchanged missives as their forces faced each other across Charleston Harbor. The Confederate commander argued repeatedly that, contrary to his initial threat, the 50 Union prisoners in Charleston were not, in fact, being subjected to friendly fire. He even transmitted a letter from the Union generals themselves, testifying that they were safe, comfortable, and being treated humanely. The prisoners suggested an exchange of their group for 50 Confederate officers of similar rank and the idea was eagerly supported by their captor, MajGen. Jones.

But all parties knew that Union General-in-Chief Halleck had ordered just a few months before that there would be no more prisoner exchanges because he believed it would only tend to prolong the war. Gen. Halleck was also acting on the recommendation of Gen. U.S. Grant who said that it would be cheaper to feed Rebel prisoners than to fight them.

But on July 29th, 1864 on the recommendation of MajGen. Foster, the U.S. Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, relented and agreed to a one-time “special exchange” of the two sets of 50 officers. (For a complete list of “The First 100,” see this blog post.) Tensions eased and the exchange took place in Charleston Harbor on August 3rd. But the relative calm was to last only one day.

On August 4th, 1864 Union MajGen. Foster received information that an additional 600 Union prisoners, all officers, had been moved from a southern prison into the city of Charleston.

As one might expect, MajGen. Foster was outraged. Not only were 600 more Union prisoners apparently being used as unwitting pawns, but MajGen. Foster himself doubtless felt the victim of a game. MajGen. Foster’s conclusion, of course, was that the Confederate general was intending to force another exchange.

The exact number and location of the 600 Union officers is a matter of some debate. Southern newspapers insisted, of course, that there were no such officers and that Union claims to the contrary were merely an attempt to justify bombing Charleston’s civilian population. Although no list of their identities survives to this day, first-hand accounts numbered the new group of Union officers at least in the hundreds and said that they were packed into A-frame tents in the courtyard of the city jail.

One of them was certainly Jacob S. Deihl (aka Devine), who had enlisted as a Private in Co. H, 71st Pennsylvania Infantry on 9 August 1861 and rose steadily through the ranks. As a 1st Lieutenant, he was captured on the 3rd day of the Battle of Gettysburg. He was confined in a series of Confederate prisons, including Macon, Andersonville, and Libby before he was transferred to Charleston. In a letter dated 30 July 1864 from Charleston, Deihl said “my health is good but d- tired of this prison life we have been shoved very near all over the Southn Confed’y and have brought up here.”

Confederate MajGen. Jones himself acknowledged the presence of additional Union officers in the city but without stipulating their names or number. He insisted that the transfer of more prisoners to Charleston had been over his strenuous objections. According to the Confederate general, they were sent to Charleston in order to relieve overcrowding elsewhere, not with the purpose of subjecting them to friendly fire.

Union MajGen. Foster had reason to believe him. In fact, he wrote to Gen. Halleck on August 4th, 1864 that Gen. Sherman’s campaign through Georgia threatened all of the southern prison camps and made Charleston “the only secure place” that the enemy could hold these officers. What’s more, he informed Gen. Halleck two weeks later that he knew exactly where the Federal officers were being held in Charleston and that he could therefore direct his shells to other parts of the city. He nonetheless requested that 600 Confederate officers be transferred to him from northern prisons in “retaliation.”

Once again, the Confederate officers were drawn from Fort Delaware. When the names were called, those officers were overjoyed. They knew of the previous exchange and expected that theirs would be a similar fate. A few who were not selected even paid fellow captives to switch places with them. But buying their way onto the list was a decision that those officers would come to regret. Not only were the 600 not exchanged, but they suffered some of the most cruel and inhumane treatment of POWs that would be documented throughout the war. In fact, the deprivation and mistreatment was so severe that this group of Southern officers would come to be revered in the Southern press as …

The Immortal 600

The 600 Confederate officers left Fort Delaware aboard the Federal steamer Crescent City on August 20th, 1864. The prisoners included officers from each of the 11 seceded states plus the border states of Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri.

Of the 600, as many as 330 (or 55%) of those Confederate officers had participated in the Battle of Gettysburg and 51 of them had been captured there. (The list of 51 is included on this blog post and the complete list of “The Immortal 600” is on this blog post.)

The ranks of the Confederate officers broke down as follows:

| Rank | Quantity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonel | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Lt. Colonel | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Major | 16 | 2 | 1 |

| Captain | 180 | 100 | 15 |

| 1st Lieutenant | 179 | 108 | 18 |

| 2nd Lieutenant | 201 | 109 | 15 |

| 3rd Lieutenant | 11 | 7 | 2 |

| Sergeant Major | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 6002 | 330 | 51 |

Of the 51 who had been captured at Gettysburg, the most senior was Confederate Major William Worthington Goldsborough of the 1st Maryland Infantry CSA (aka 1st or 2nd Maryland Battalion and the 2nd Maryland Infantry). In October, 1859, as an officer in the Baltimore City Guard Battalion, Goldsborough had been one of the first to enter the armory at Harper’s Ferry to capture John Brown.

When war broke out, Goldsborough’s state of Maryland was split in its loyalties - and so were the members of his family. William enlisted in the Confederate army in May of 1861. His brother, Charles, was practicing medicine at Hunterstown, PA, just a few miles north of Gettysburg. In November of 1862, Charles enlisted as a surgeon in the 5th Maryland Infantry USA.

The brothers next met at the Battle of Winchester on June 15th, 1863, where the 1st Maryland CSA faced the 1st Maryland USA and other Union regiments. Then-Captain William Goldsborough had the distinction of capturing his brother, Charles, who was then sent to Libby Prison. Charles was exchanged and returned to duty later that year.

In the meantime, the Confederate brother took command of the 1st Maryland CSA at Gettysburg when Col. Herbert was wounded during the assault on Culp’s Hill on July 3rd, 1863. As the Confederates fell back, Maj. Goldsborough was shot through the left lung and captured. He was sent to Fort Delaware where some months later he had another reunion with his brother Charles, who was coincidentally assigned as a surgeon to that post. In September of 1864, William said goodbye to his brother as he was shipped off to Charleston Harbor. They wouldn’t meet again until after the war.

Bound for Charleston, the 600 Confederate officers, including Maj. Goldsborough, faced the worst conditions that they had yet encountered as prisoners. Forced to lie shoulder-to-shoulder in the ship’s hold below the water line, one prisoner said that they lay in “total darkness, without any clothing and drenched in perspiration” from the summer heat which was intensified by the ship’s boilers. As the Crescent City rolled in rough seas, all of the prisoners became seasick, leading one on board to describe the ship’s hold as “a veritable cesspool” which the Union guards refused to hose down. In this environment the Rebs were fed just a “few crackers with a bit of salt beef or bacon” per day. Drinking water was likewise scarce, said one prisoner, and it “had a disagreeable smell and a very sickly taste.”

Also among the Gettysburg veterans on board was Capt. Thomas W. Kent, of Co. F, 48th Georgia Infantry. Capt. Kent had led his company when Wright’s Brigade charged across the Emmitsburg Road at Gettysburg on July 2nd, 1863, capturing guns and prisoners in the vicinity of the Codori House. The Brigade continued towards the Federals, breaching the line at the Angle, and reaching the crest of the Cemetery Ridge before they were forced to retreat with heavy losses. Among them was Capt. Kent, who was wounded in the right hip during the charge and captured.

Capt. Kent spent the next 16 months confined in a series of northern prisons, the last of which was Fort Delaware. Before long he found himself sailing south on the Crescent City.

In the last days of August, 1864 the steamer and its 600 Confederate prisoners arrived at Port Royal Harbor, South Carolina, about 50 miles beyond Charleston. About 40 of the prisoners who were severely disabled by wounds or disease, including 14 who had been captured at Gettysburg, were taken off the prison ship and sent to a nearby hospital in Beaufort, South Carolina.

While the ship was anchored at Port Royal, Capt. Kent and seven of his comrades managed to acquire life jackets and jumped ship. Capt. Kent and some of the others made it to Hilton Head Island and then to Pinckney Island at the mouth of the harbor before they were recaptured and returned to the Crescent City. It wouldn’t be Capt. Kent’s last escape attempt.

As they sailed back north to Charleston, the balance of the Confederate officers managed to suffer through the squalid conditions of the Crescent City by maintaining the faith that they were sure to be exchanged upon reaching their destination. Even as the steamer reached the vicinity of Charleston Harbor and the prisoners were forced to remain on board for another five days, the officers told themselves that the details of exchange were being worked out. But their ordeal had only just begun.

They were soon to discover that the delay in disembarking on Morris Island was due to the fact that the construction of their 1.5 acre “pen” or open-air stockade had not yet been completed. After a journey of 18 days, the Confederate officers stepped onto Morris Island on September 7th, 1864, not knowing that they were leaving one hell and entering into another.

They were met on the wharf by the remnants of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, who had unsuccessfully assaulted Fort Wagner 14 months earlier. The irony didn’t escape the enlisted men of the 54th who were now charged with guarding Rebel officers on that same small island. For their part, the Confederate officers felt that they were being deliberately disgraced by the assignment of black guards. They saw it as yet another provocation to compound their ill treatment as prisoners - and all within the tantalizing sight of the Confederate city of Charleston.

That torment must have been especially intense for 2Lt. William Swinton Bissell of Co. A, 2nd South Carolina. He suffered a fractured fibula in his right leg on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg and was captured. After confinement in a series of northern prisons, Lt. Bissell had the misfortune of landing at Fort Delaware where he was selected to be among the Immortal 600. Lt. Bissell was living in Charleston when the war broke out. Now he found himself straining to see through the gaps in the stockade fence at his home town which was just beyond his reach.

As Union MajGen. Foster promised, the prisoners’ stockade was on the extreme northern end of the island, directly in the line of fire from Rebel guns and exposed to errant fire from Fort Wagner. They were housed in groups of four in A-tents which proved little protection from the weather, much less from the sand fleas and mosquitos that were common in this marshy land. And, of course, there was no protection whatsoever from artillery fire.

An officer from Virginia recalled, “Oh, the misery of having the ear constantly filled with such doleful sounds, the misery, the horrible misery, the wretched agony of anticipating death at every moment!” Another remembered that in another exchange of fire, “Two shells did prematurely explode, throwing huge pieces into our camp, many fragments flying just over our heads, and one of the shells exploded the huge gun, killing a horse and cutting off a man’s leg. One of the pieces buried itself in the wall behind my head, whilst a number of pieces fell in the street between us and the fence; another struck within two inches of Captain Lewis, five tents distant from us.”

Lt. James Edward Cobb of Co. F, 5th Texas Infantry (a future U.S. Congressman) had been wounded in the hand and captured during his regiment’s attack up the slopes of Little Round Top at Gettysburg. He was confined at Fort McHenry, Johnson’s Island, Point Lookout, and then Fort Delaware before he was picked as one of the “lucky” ones to join the 600.

One morning Lt. Cobb was in a small tent with three other officers when “a large shell fell right at our feet and covered us all with sand but fortunately did not explode.” Remarkably, under the circumstances, none of the officers on Morris Island were killed by artillery fire.

In the early days of their ordeal on Morris Island, the officers were given half army rations but food and water quickly became more scarce and in much worse condition. A Virginia officer lamented, “For rations we were furnished three army crackers per day, and a half pint of soup … It was called bean soup but we never discovered any traces of that vegetable in the mixture.” An officer from Missouri wrote, “Water full of wiggle-tails today” and “Rations for breakfast two ounces old salt beef, so badly spoiled that we could not eat half of it. Three crackers, musty and full of worms - not fit for hogs.”

Capt. George W. Nelson was on the staff of BrigGen. and Chief of Artillery William Pendleton and was a veteran of Gettysburg. He wrote about the “lively nature” of the bread: “For my own part, I was always too hungry to be dainty - worms, mush and all went to satisfy the cravings of nature.” He witnessed some who, after picking out between fifty and eighty worms, stopped picking them out because “a little bit of mush was going with them.”

According to a North Carolina officer, “Some of the prisoners, for the sake of the record complained to the colonel. He replied that it was all right; there was enough meat in the meal, bugs, and worms, and that if he had his own way he would be only too glad to feed us on greasy rags.”

Although nearly every officer suffered from dysentery, chronic diarrhea, scurvy, and/or pneumonia, only three died of disease while imprisoned on Morris Island. One was Lt. John C. C. Cowper of Co. E, 33rd North Carolina Infantry, who had been severely wounded in the right lung and shoulder during Pickett’s Charge and captured at the Seminary Hospital near Gettysburg. He spent the next 16 months being transferred between northern prisons. He continued to suffer from the gunshot wound and spent much of that time in prison hospitals. At Morris Island the poor diet did not help him to recover, and pneumonia eventually took him on October 14th, 1864. According to the Provost Martial he was buried in a marked grave on the island but the site has long since been lost.

The standoff continued on Morris Island for 45 days. When yellow fever broke out in the city of Charleston, the imprisoned Union officers were moved to newly-erected prison camps further to the west. About the same time, the decision was made to remove the Confederate officers from Morris Island.

In the early morning of October 21st, 1864 the surviving Confederate officers were marched down the beach under guard to two waiting schooners. The stubborn hope among the men was that they were finally to be exchanged. But they would soon discover that their destination was Fort Pulaski on Cockspur Island, Georgia, about 75 miles down the coast.

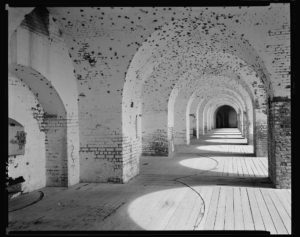

Fort Pulaski at the mouth of the Savannah River had been completed in 1847 as a defense against overseas enemies. It became a Confederate stronghold at the beginning of the Civil War. With walls ranging from 7.5 to 11 feet wide, it was considered impenetrable by the short-range, smooth-bore cannon of the time. Part of its construction had been overseen by recent West Point graduate 2nd Lt. Robert E. Lee who remarked that “one might as well bombard the Rocky Mountains as Fort Pulaski.”

But on April 10th, 1862 the Union army about a mile to the east on Tybee Island had a new weapon - long-range rifled cannon - and in only 30 hours it reduced some parts of Fort Pulaski to rubble, exposing the 40,000 pounds of black powder in its magazine to the risk of direct fire. The Confederate commander, realizing that another well-aimed shot could destroy the fort and kill every defender, raised the flag of truce. Union attackers quickly took possession of the fort, effectively blockading the important port city of Savannah. In the Fall of 1862, it was converted to a Union prison.

In their first hours upon arriving at Fort Pulaski, the Confederate officers of the Immortal 600 thought that they had gone to heaven. They were housed inside the fort’s casemates which were cold and damp but they had stoves and were promised blankets. They felt protected from the approaching winter and they were no longer in the direct line of fire. Perhaps more importantly for their survival, their first meal was “a feast fit for the gods,” as one Confederate officer put it. He went on, “It consisted of excellent white bread, good fat meat, and a big tin of delicious vegetable soup, with lots of grease in it. After getting settled in the fort, with splendid cisterns of good drinking water, we began to think that our troubles and woes had ended.” Adding to their relief, they found themselves guarded by the white soldiers of the 157th New York Infantry.

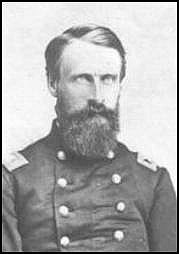

The Union officer in charge, Col. Philip P. Brown, promised to make the fort “the model military prison in the United States” and he was as good as his word. Or so it seemed at first.

When word of this civilized treatment reached his commanders, Col. Brown received orders to place the prisoners on a starvation diet in retaliation for the treatment of Union prisoners in Andersonville and other Confederate prison camps. Reluctantly, Col. Brown followed orders and the prisoners were thereafter fed no meat or fruit which led to an outbreak of scurvy and diarrhea. For six weeks their diet consisted only of rancid cornmeal and pickles.

By November, 1864 the weather turned bitterly cold and the promised blankets never materialized. The officers had only their summer clothes that they brought to Fort Delaware in August and the stoves were only equipped with enough fuel for cooking. Many men contracted pneumonia and scurvy, but the prison doctor was not permitted to give them any medicine except opium as a painkiller. As a result, some of the officers became addicted to opium.

One such sad case was 1Lt. George P. Fitzgerald of Co. A, 12th Virginia Cavalry. “Fitz”, as he was called, was a proud graduate of West Point who had been captured on July 8th at Gettysburg.3 Another veteran of Gettysburg, Capt. Henry C. Dickinson of Co. A, 2nd Virginia Cavalry described “Fitz” at Fort Pulaski as “a confirmed opium eater; a poor miserable wreck — ragged, filthy, lousy, loathed by all, and pitied by many, who reported sick that they might get opium for him. He has no blanket, no socks, hardly clothes to cover him”.

On November 13th, Lt. Fitzgerald’s death of pneumonia and chronic diarrhea came as no surprise to anyone. Before their ordeal was over, another 12 Confederate officers would meet the same fate within the walls of Fort Pulaski. All but one of them were veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg and four of them had been captured there.

To their credit, many of the captors were sympathetic to the plight of the Confederate officers. The prisoners recalled that Union Col. Brown himself extended every courtesy that his strict orders would allow and that the Colonel “was much moved, and his voice tremulous when he informed us [of his orders] but he attempted to cheer us, stating that he hoped that the cruel treatment would be of short duration.” Members of the 157th New York Infantry who were guarding them likewise did what they could to ease the suffering. Some handed feral cats through the bars of the prison knowing that the starving prisoners would kill and cook them. Some of guards “would put a loaf or piece of meat on the end of their bayonets and dare any Rebel to take it off”, but when they did, there were no repercussions, wrote one prisoner. He went on, “These men took this method of helping us and getting around their orders. They dare not openly disobey.”

In late November Col. Brown determined that Fort Pulaski was overcrowded so he moved nearly 200 of the remaining “Immortal 600” to a prison on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, about 10 miles up the coast. In conditions similar to those which they had experienced on Morris Island, Lt Peter B. Akers, a veteran of Gettysburg, wrote, “The pangs of starvation became terrible; hunger drove our men to catching and eating dogs, cats, and rats.” Hilton Head Island took the lives of four more Confederate officers.

For two of them (Capt. William Bailey, Jr., of Co. G, 5th Florida Infantry, and 1Lt. Robert B. Carr of Co. A, 43rd North Carolina Infantry), it was the end of a long ordeal which had started with their capture at Gettysburg.

On Christmas night, 1864, seven of the remaining officers at Fort Pulaski began working on a plan to escape. Among them was Capt. Thomas W. Kent, who had led the ill-fated attempt to escape by jumping ship at Port Royal four months earlier.

The men had discovered a trap door leading to a lower chamber of Fort Pulaski that was full of water and mud. With just scraps of metal for tools and while standing in waist-deep freezing water, the starving men began tunneling through the brick foundation of the fort. After nine weeks, the men had tunneled through 336 feet of brick and mortar. On February 28th, 1865 the tunnel was complete and Capt. Kent was the third man to make it through the walls. They reached the wharf where they planned to steal a boat but just as they were about to overwhelm the guard, one of their number (Capt. Rufus C. Gillespie of Co. G, 45th Virginia Infantry) shouted out, “Don’t shoot”, and gave them away. The seven were quickly surrounded and returned to the prison where they were placed in manacles in their cold, wet clothes for five days as punishment.

On the March 4th, 1865, the prisoners received orders to prepare to move. Very soon they were marched two-by-two out of the gates of the fort and to the wharf where they boarded the Federal steamer Illinois with the promise to be exchanged. They set sail to the north, stopping at Hilton Head Island to pick up their comrades who had been moved there.

A few were left behind with the expectation that they would not survive the voyage. One was 2Lt. Absalom H. Farrar of Co. C, 13th Mississippi Infantry who had been wounded in the right foot before he was captured on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg. He had been moved to the hospital in Augusta, Georgia, where he died on February 1st, 1865.

The voyage ended at Fort Delaware, completing a round trip for those who had survived, but as with many times before, no exchange was waiting for them. Three more officers had died on the voyage north on the Illinois. Remarkably, three more stowed away when the ship reached Fort Delaware, including Capt. Leon Jastremska, a veteran of Gettysburg who served with Co. E, 10th Louisiana. When the ship later arrived at New York City, they escaped.

Immediately upon arrival at Fort Delaware, 75 of the officers were sent to the post hospital because of their dire condition. 18 of them died there. Gettysburg veteran Capt. John J. Dunkle Co. K, 25th Virginia Infantry spoke of the Fort Delaware prisoners who had not made the trip when he said, “Our comrades scarcely knew us, so changed were our features, and so haggard our countenances.”

Result of Captivity - Immortal 600

| Result | All | GB Veteran | Captured at GB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Died on Morris Island | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Died at Beaufort Hospital, SC | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Died at Fort Pulaski, GA | 13 | 11 | 4 |

| Died at Hilton Head, SC | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Died on board the steamer Illinois | 34 | 0 | 0 |

| Died at Fort Delaware, DE | 18 | 10 | 2 |

| Died at Hospital, Augusta, GA | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Died at home soon after of effects | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Survived Captivity | 554 | 303 | 40 |

| Total: | 600 | 330 | 51 |

Despite their hardships and deprivations, most of the surviving Confederate officers refused to take the oath of allegiance to the United States during their ordeal, even knowing that to do so would have eased their suffering. Even by May 2nd, 1865 when they knew of the final defeat of the Confederacy, many refused to “swallow the yellow dog” and swear their allegiance to the victors even though it was a condition of their release. The last holdouts finally complied on 24 July 1865, nearly 3 months after the end of the war, and were released.

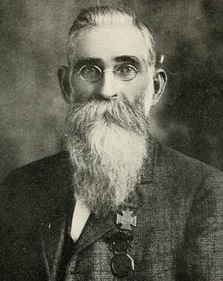

At a Confederate reunion in 1905, two former officers of the 25th Virginia Infantry, 1st Lt. Junius Lackland Hempstead (Co. F) as President, and Capt. Jacob W. Matthews (Co. I) as Vice-President, founded the Society of the Immortal Six Hundred with Capt. John Ogden Murray, (formerly of Co. A, 11th Virginia Cavalry) as its Secretary. All three were veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg. (In the same year, Capt. Murray published his extensive first-hand account of his experiences, cited among the sources at the end of this post.)

The purpose of the Society of the Immortal Six Hundred was to “to help, so far as we can, in a practical way, and minister to the wants of our comrades and members of the Six Hundred who remained true unto the end of the ordeal of fire and starvation.”

The bylaws of the Society further stipulated that their purpose was to “keep alive the story of our terrible days on Morris Island as prisoners of war and the inhumanity and brutal treatment inflicted upon us by the United States Government, and give to our children and the world a true history of our tortures on Morris Island, South Carolina, and subsequent brutal treatment at Fort Pulaski, Georgia, and at Hilton Head, South Carolina”.

The last known survivor of the Immortal 600, 2Lt. William Epps of Co. D, 4th South Carolina Cavalry, proved mortal after all on November 12th, 1934.

On May 21st, 2012 the National Park Service erected a wayside marker and a monument at Fort Pulaski, Georgia, summarizing the experience of the Immortal 600 and listing the names of the 13 Confederate officers who died at that fort.

1Throughout this post, “veteran of Gettysburg” means that the officer’s regiment was at Gettysburg. It is possible that some individual officer(s) were in a hospital, on furlough, or otherwise not personally engaged in that battle.

2Two of these “officers” may actually have been enlisted men. See Edward S. Hart and William P. Johnson on the full list.

3This officer’s rank, regiment, and date/place of capture are in dispute as his Compiled Military Service Record is inconsistent on all of these points. See his entry in the list above.

4One of these officer who died on board the Illinois was not identified by name.

Sources and further reading:

- The Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS), National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm

- FindAGrave tombstone photos, www.FindAGrave.com

- “Immortal 600: Prisoners Under Fire at Charleston Harbor During the American Civil War” HistoryNet, web site.

- “Imprisoned Under Fire”, Richmond Times Dispatch, 22 Aug 1897, pg6, as reprinted in Southern Historical Society Papers, v25, Jan-Dec, 1897.

- Joslyn, Mauriel Phillips, Immortal Captives (Gretna, LA: White Mane Publishing Co., Inc., 2008).

- Joslyn, Mauriel, The Biographical Roster of the Immortal 600 (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Co., Inc, 1991).

- Kaufmann, Patricia A., “The Immortal 600: Exceedingly rare covers help tell the Civil War story of horrid retaliation and retribution”, The American Stamp Dealer & Collector, April, 2009, p19, pdf file.

- Murray, J. Ogden, The Immortal Six Hundred (Roanoke: The Stone Printing and Manufacturing Co., 1911).

- Pearce, T. H., “The Immortal 600”, Confederate Veteran, Vol. XXXIV, No. 1, Jan-Feb, 1986.

- “Prison Experience of a Confederate Soldier”, Bristol Courier, 14 Sep 1893, as reprinted in Southern Historical Society Papers, v22, Jan-Dec, 1894.

- “Prisoner of War Experience”, National Park Service, web site.

- “The Prisoners of War: The Immortal 600, Charleston, S. C.”, web site.

- Stokes, Karen, The Immortal 600: Surviving Civil War Charleston and Savannah, (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2013).

- Speer, Lonnie R., Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War (Lincoln, Nebraska: Bison Books, 2005).

- Speer, Lonnie R., War of Vengeance: Acts of Retaliation Against Civil War POWs (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002).